It’s been more than six years, but Suad Abdelaziz still cannot believe what happened to her cousin.

In June 2016, a US court found 25-year-old Muhanad Badawi guilty of “aiding and abetting the attempt to provide material support” to the Islamic State (IS) group.

According to prosecutors, her cousin had purchased a one-way ticket for his friend, Nader Elhuzayel, to travel to Syria to join IS.

The Department of Justice said both men had drawn the interest of law enforcement interest in 2013, after posting several messages of support for IS on social media. They were subsequently monitored, and when Elhuzayel purchased a one-way ticket to Turkey via Israel, they were both arrested and charged.

But 28-year-old Abdelaziz says the case was bogus.

She says Badawi loaned his credit card to a friend. He didn’t know that Elhuzayel was allegedly joining IS. “I say allegedly because the state did not prove that he was joining IS either,” she told Middle East Eye.

Instead, she claims, prosecutors used the two men’s comments on social media to establish anti-America animus and relied on jury prejudice against Muslims to conclude they were terrorists.

Both men pleaded not guilty to the charges of terrorism but were convicted and sentenced to 30 years each. The trial lasted two weeks.

“They [the courts] don’t need evidence of specific intent to commit or support a violent act. They just need to establish that the person has knowledge that these organisations are considered terrorists,” said Abdelaziz, who is now finishing her third year of law school and is an intern for Palestine Legal, a civil liberties organisation in the US.

Badawi’s story is just one of several hundred concerning Muslim Americans who have been targeted by authorities and incarcerated over spurious and vague charges under the prism of the “war on terror.”

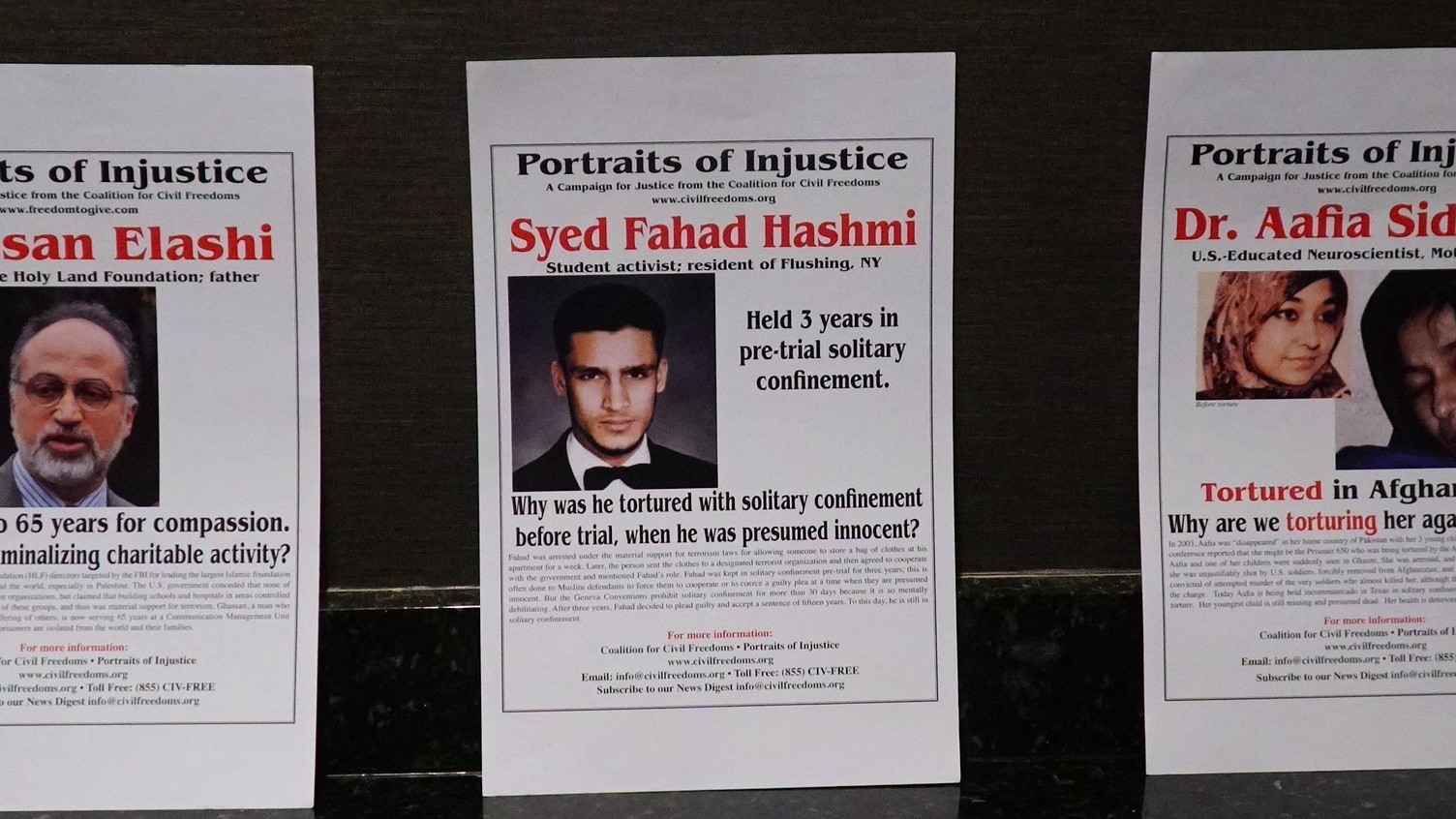

At a conference organised by the Coalition of Civil Freedoms (CCF) in Washington DC over the weekend, dozens of American Muslims, like Abdelaziz, gathered to discuss the fate of their loved ones, who have either faced surveillance, imprisonment, or periodic harassment from authorities.

Families and activists at the conference say the prisoners are the forgotten ones, often abandoned by the American-Muslim community for fear of being accused of terrorism themselves.

It’s not hard to see why.

As part of the “war on terror”, the American government targeted mosques and local political leaders, often incorporating Muslim institutions into its wide net of counter-terror policies that pathologised the Muslim community.

“To date, the US government, through the Department of Homeland Security’s various programmes – in the past CVE/TVTP, and currently rebranded as CP3 – continues to target communities through racial and religious profiling with various tactics including providing grants to Muslim organisations,” Sarwat Malik-Hassan, political advocacy director for CCF, told MEE.

“With the grants pushed and taken by the community organisations, including mosques and Islamic centres, the government is able to have access to space which was supposed to be otherwise sacred and safe.”

Malik said that many Muslim groups and leaders, including those who brand themselves as civil liberties groups, are pushing mosques to apply for these grants, conducting workshops and trainings to facilitate the community in having careers with law enforcement and the FBI.

“This leads to mistrust from the community, and specifically from those who are impacted. It leaves them isolated because a clear message is being sent, that those sacred spaces have chosen to be complicit with the very system that has unjustly incarcerated their loved ones. They are ‘un-communitied’ and ‘un-mosqued’.”

The forgotten ones

The United States declared its global “war on terror” in response to the 11 September 2001 attacks in New York and Washington, and subsequently invaded Afghanistan and Iraq, leading to close to a million deaths worldwide.

In the US, the administration of George W Bush introduced the Patriot Act, which gave law enforcement almost free reign to target anyone deemed to be a threat to the United States.

Thousands of American Muslims were surveilled, targeted in cases of entrapment, or prosecuted for aiding and abetting terrorism.

Nada Dibas, prisoner and family support coordinator with CCF, said that one of the goals of the conference, now in its 11th year, was to provide the community with the tools to share their stories and shift the narrative.

“These families really need help. We really wanted to help them become their own advocates.

“Everything that we picked was along the lines that ‘help is not coming’ and it’s simply us and if we don’t do it, no one is going to do it. So this conference was about empowerment.

“We can’t sit around and expect things to change. It’s on us to demand otherwise,” Dibas added.

On Friday, the families gathered within walking distance of both the Department of Homeland Security and Immigration and Customs Enforcement – two institutions created post-9/11 and often used to target members of the Muslim-American community.

Sessions at the event ranged from one addressing grief to another focused on crafting a narrative, led by award-winning filmmaker David Riker, the co-writer of the acclaimed documentary, Dirty Wars.

“Terrorism is a really taboo thing to talk about and it’s designed that way [and] is designed to chill us from speaking to one another to create a culture of fear in our communities. And a gathering like this is just revolutionary in itself,” Abdelaziz added.

Hesham el-Meligy, who has organised and advocated for political prisoners for almost two decades, described the meeting as “therapeutic”.

“This was therapeutic to put it in a human way, because it is very hard, very isolating, very demoralising to feel the entire weight of the federal government with all its power on your back, and you cannot even talk openly about it.”

Likewise, former prisoner Ahmed Hassan* told MEE that the conference was among the rare occasions he could meet with people who understood the isolation that came with being accused of terrorism.

Hassan, 22, who spent five years in prison after a court ruled that his social media amounted to providing “material support” to IS, told MEE that his family was abandoned and ostracised by the community following his arrest seven years ago.

On the advice of his lawyer, he pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 11 years and three months in jail. In 2019, the Department of Justice reduced Hassan’s sentence to five years. His case, however, is still sealed and Hassan still faces restrictions over his internet use.

“This particular experience of being accused of being an enemy of the state is unique and designed to be isolating. Here, we can talk about our experiences,” Hassan said.

On Monday, families, along with organisers of the CCF, met with representatives on Capitol Hill to lobby lawmakers to introduce the Entrapment and Governmental Overreach Relief Act, or the EGO Relief Act.

The bill seeks to prevent the US government from basing entire criminal cases on the use of informants and entrapment, and also apply retroactively to previous cases. Meligy said he hopes the efforts will result in educating and motivating members of Congress to correct the wrongs of the past.

“The chances that this happens at all, or happens fast, is almost zero, but we have to start somewhere,” Meligy said.

Abdelaziz says her family has no option but to hang on to hope.

“More people are recognising that the “terror” label has to be re-conceptualised. There is more awareness of state-sponsored violence and that who is called a terrorist and who is not, is all about power.”

Abdelaziz called the conference “truly empowering”.

“I think I’ve been hopeless for a while. And [the conference] has given me a lot of hope that with enough people that speak about their stories, and more than enough people to support and be in solidarity with these prisoners, is going to eventually create change.”

*Name has been changed.

Post Disclaimer

Disclaimer: The forgotten Muslim-American families wounded by the 'war on terror' - Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Latheefarook.com point-of-view