Jayathilaka and mother Dingiriamma

The journey has been long––very very long. It started in a little village called Dandu Bendi Ruppa, in Nuwara Kalaviya, when Dingiriamma rolled Jayathilaka in a ‘borrowed’ wheelchair for his first day in the village school. “Hodatama Wahinawa Mahaththayo” she told me–– the skies were gray and raining and the distant clouds were coughing thunder. She had covered her 10-year-old handicapped son with a plastic sheet and pushed him on rickety old wheels, gifted to them when an old man died in the next village. Such was the beginning ….

That was then, 25 years ago.

The ceremony was solemn, opulent and almost sacred. The National University of Singapore does not spare anything when it comes to their ‘lime-light’ events. The Class of 2011 all gathered in their robes of black and flat hats, mostly young, ‘this medal winner’ and ‘that medal winner’ of Singapore’s best brains in youth. The recipients of the prestigious degrees totalled more than 400. Then there were the chosen few representing the elite in education, the ones who had read and completed their PhDs in this world-renowned institution. The audience gathered was the ‘who’s who’ of Singapore in their Saville Row suits and Bally feet. Pahalagedara Jayathilaka, too, was there, sitting among the Doctors of Philosophy, his crutches folded across his knees waiting to be called to end his unbelievable journey.

The ceremony was solemn, opulent and almost sacred. The National University of Singapore does not spare anything when it comes to their ‘lime-light’ events. The Class of 2011 all gathered in their robes of black and flat hats, mostly young, ‘this medal winner’ and ‘that medal winner’ of Singapore’s best brains in youth. The recipients of the prestigious degrees totalled more than 400. Then there were the chosen few representing the elite in education, the ones who had read and completed their PhDs in this world-renowned institution. The audience gathered was the ‘who’s who’ of Singapore in their Saville Row suits and Bally feet. Pahalagedara Jayathilaka, too, was there, sitting among the Doctors of Philosophy, his crutches folded across his knees waiting to be called to end his unbelievable journey.

I sat with Dingiriamma, his mother, along with his brother and sister-in-law, whom he had brought down from Sri Lanka to witness the final walk. This sure was a different planet to these rural people and they sat in their village innocence, making feeble attempts to come to terms with the grandeur of it all. If anybody had a right to be there, it sure was Dingiriamma. The name was announced, “Pahalagedara Jayathilaka” and I glanced at the 70-year-old mother and saw her staring ‘blink-less’ as her beloved son walked on to the stage. Eyes glued and tears pouring down a mottled skinned cheek as she celebrated, with absolute awe, each step Jayathilaka was taking, crawling the final crawl in crutches to receive his PhD.

What enormous battles she had fought along with him? What roads they had walked together, poor pilgrims in an unknown odyssey? Hand in hand and crutches clinched, they trudged the unimaginable tortuous steps of a very long journey that had impossible mountains to climb. What wringing they would have done to squeeze out the drops of courage from their dented and battered lives to see the far distant light and to be where they are today?

“How many roads must a man walk down, before you can call him a man?” the immortal words of Dylan come to my mind. The answer is not in the wind, but in the unbelievable achievement of Jayathilaka who had surmounted all obstacles to stand tall today with his ‘Fluid Dynamics’ doctorate. The other side of the coin, of course, is Dingiriamma, the simple uneducated mother who cultivated vegetables and raised him with eight other siblings, as a single parent, in an obscure village. What visions would she have of education? What ambitions would she have hoarded as all other mothers do for their sons? What hopes? What ways to even think of him attending school let alone entering a university? She had only the purest of love in a cruel world of ‘cripple-look-down.’ “Mata dukai Mahaththayo, abbagathayekne,” she just wanted to make the little disabled boy play some little part in life other than to be an intrinsic failure with lame legs. That was her call to give her son some normalcy. Dingiriamma, when she pushed the wheelchair to school on the first day, in the pouring rain, would never have thought in her wildest dreams how far this brilliant young man would travel along his long and gruelling trail.

Yes, the old unheralded mother sat among the elite of Singapore, a poor vegetable seller from a village near Dambulla, dressed in a pale brownish white sari, a long necklace of metal and some coloured beads around her neck, and a hanky to constantly wipe her eyes, watching a very rare impossible dream take form and shape in reality.

“The bravest battle that ever was fought

Shall I tell you where and when?

In the maps of the world you would find it not

It was fought by the mothers of men.”

I am sure all you mothers who read this article will silently cheer Dingiriamma, applaud her in your hearts and sing her praises to those you meet. She certainly deserves that and more, the unknown and unsung optimum of motherhood which she in her own simple way displayed in almost unparalleled achievements of emotion filled courage and has unknowingly laid bare for others to emulate.

It was Jayathilaka who told me he had heard on his first day in school one teacher telling the other, “Why is this cripple allowed here? He is going to be a problem’, and the other teacher saying ‘Maybe he can at least learn to write his name.” That he remembers well along with the other almost ‘fairy tales’ he told me of his childhood and the way he scrabbled to where he is today.

Jayathilaka received repeated double-promotions and he went from the village school to Kurunegala to do his A/Ls, where he scored the highest marks in the district and entered Katubedde University to study Mechanical Engineering.

That part had been extremely difficult, Dingiriamma’s meagre earnings, from selling vegetables, was hardly adequate to support young Jayathilaka. His best eating had been a ‘banis or a malu paan’ at Mallika Bakery and the ‘food-festivals’ they laid out on campus to those who survived on subsidised meals.

I had very close interactions with him at this time. By then he had joined CandleAid Lanka as a sponsored student. I do remember asking him in his last year how he was faring in his Uni work and how he answered in a humble tone “Captain, I am sure of a First Class.”

How many…

That bowled me completely. Here was a handicapped student crawling in crutches and broke as the ‘ten commandments’ and yet ‘dead-certain’ of his unamplified ability to obtain a First Class Honours degree in the subject he was reading.

Jayathilaka did not get a First Class––what he received was a Super First Class. I did not even know what that meant, but my basic English told me it was better than a First Class.

The journey is now over; Dingiriamma has done her part as a mother to bring her little handicapped boy to where he is today. He, too, has done more than his share, where much more able people would have given up even before they began, Pahalagedara Jayathilaka plodded on to a golden finish line.

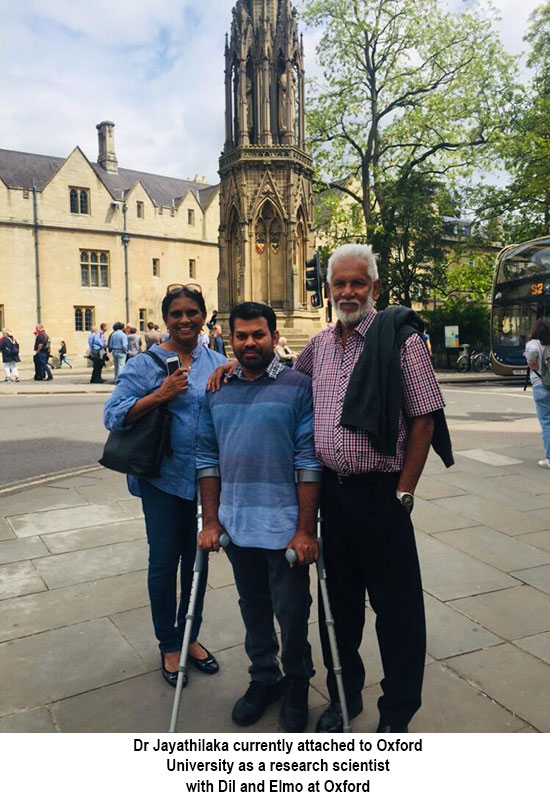

Dr. Jayathilaka has been offered employment at the National University of Singapore as a postdoctoral researcher. He will continue there for two more years.

“I want to go back, I like to teach in Sri Lanka, I owe that to my homeland that gave me a free education,” such were his words after the ceremony, spoken in true patriotic vein, sincere and laced with gratitude.

That night we gathered and shared a simple meal to celebrate. They had brought ‘kalu dodol’ from home with just the right Nuwara Kalaviya touch. There was no one to interview them; nor were there flashing lights and TV cameras to record their story. Dingiriamma recalled some of the stories of Jayathilaka’s childhood; how he used to crawl around the table when the others were studying and how his brother taught him to write. And how he went to school pushed in his ramshackle wheelchair and how he painfully walked small distances bending and lifting his bad leg with his hand to take a few steps. The conversation was all about the road they travelled, and the stories sounded unbelievable. I wish I had space to write, but then my words would be superfluous and colourless, totally incapable of capturing the full essence of their journey, let alone the accompanying emotions of the mother and son.

I wonder how Mother Lanka would recognise and praise someone like Dingiriamma. It matters not to her and it certainly matters not to Jayathilaka; they have already won their race. These are stories that should not be forgotten-––especially how a mother and son walked an extremely demanding trail from the village of Dandu Bendi Ruppa to the National University of Singapore and a PhD in Fluid Dynamics.

The shine is on them; it is for others like you and me to see and recognise the simplicity and the greatness. Pale brownish white sari, long chain with beads and hanky in hand to wipe her tears, Dingiriamma stood the tallest at the Class of 2011 celebration. As for Dr. Pahalagedara Jayathilaka in his black and green gown, clutching his crutches, he walked the proudest, yet the humblest at the ceremony, to the loudest possible ovation.

I was so privileged to be there to share that rare moment.

Post Disclaimer

Disclaimer: How many roads must a man walk down? - Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Latheefarook.com point-of-view