The region that now makes up modern-day Afghanistan has long been a crossroads of civilisation, connecting cultures in Central Asia, East Asia, the Middle East and South Asia.

After the arrival of Islam in the region, various Arab, Persian, Turkic and Mongol rulers valued the mountainous territory for its proximity to trade routes, fertile valleys, and strategic position for raids further to the south over the Hindu Kush mountains.

The Mughal Emperor Babur had his capital in Kabul before launching his invasion of India; his Timurid ancestors kept their capital in the western city of Herat, from where they controlled an empire that spanned much of Central Asia, Iran, Iraq and Anatolia.

The term “Afghan” traditionally referred to ethnic Pashtuns, but the modern state of Afghanistan includes regions that have traditionally spoken Persian dialects, known as Tajik, and Turkic languages, such as Uzbek.

Historically, the region was also home to small Arab communities, who arrived as soldiers, administrators, merchants and missionaries in the centuries following the birth of Islam, but these populations have since been assimilated into neighbouring ethnic groups.

Their existence nevertheless underscores Afghanistan’s integral position in the mediaeval Islamic world.

Here Middle East Eye looks at some of the most influential people with strong ties to Afghanistan and specifically their impact on the Middle East.

Rumi

Widely regarded as one of the greatest Persian language poets, Jalal al-Din Muhammad Balkhi, later known as Rumi, was born in September 1207, in the Balkh province of Afghanistan.

The son of a religious scholar, Rumi was himself an Islamic jurist and devoted Sufi, with much of his poetic verses devoted to understanding the nature of God.

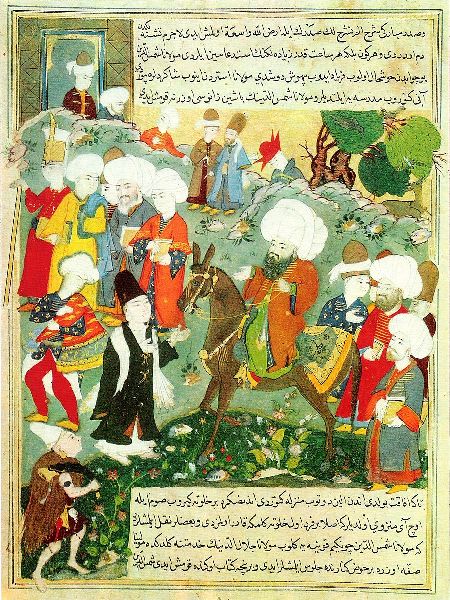

Rumi left Balkh with his family at a young age to escape the Mongol hoardes invading Central Asia, eventually living in Iraq, Syria and modern-day Turkey at different points.

As he got older, Rumi studied within the Hanafi school of Sunni jurisprudence and later moved to Konya in Turkey, in a region then known as Rum, where he worked as a teacher.

The poet was widely read in Arabic grammar and narrations attributed to the Prophet Muhammad, as well as secular subjects such as history, philosophy and astronomy. His studies earned him the epithet mawlana, meaning “our master”, variants of which are still used to refer to him today.

Rumi’s poetry explored diverse themes and were sometimes intended as spiritual instruction and at other times as entertainment.

As well as devotions to God, the fraternity of all humans and renunciation of temporal existence. There are also verses dedicated to his friend Shams Tabrizi, a fellow mystic.

His works have had a significant impact on the development of Turkish, Persian and South Asian literature, and his original verses continue to be read both in their original Persian, Turkish and Arabic, as well as in translation.

Today Rumi’s work has reached the mainstream with translations widely available in bookshops across the West, having his work being read out by Madonna, helping Coldplay’s Chris Martin get through his divorce with actress Gwyneth Paltrow, and appearing as inspirational quotes on social media.

The trend is not without its critics, with Muslims and scholars of Persian literature accusing western artists and translators of removing Islamic references in Rumi’s works and turning devotions to God into romantic poetry.

Rumi died in Konya in December 1273, aged 66, and his funeral drew thousands including believers of other faiths. A shrine over his grave remains a popular attraction for devotees and tourists alike.

Imam Abu Hanifa

Abu Hanifa Numan bin Sabit bin Zuta was born in Iraq in the year 689CE to a Persian father from Kabul. He would later go on to become one of the most influential Muslim jurists and theologians in history, best known for establishing the Hanafi school of Sunni jurisprudence, the most widely followed of the four main Sunni traditions.

As a youth, he seemed destined to follow in his father’s footsteps by becoming a merchant, but a fondness for theological debates developed into full-time study of the Islamic faith.

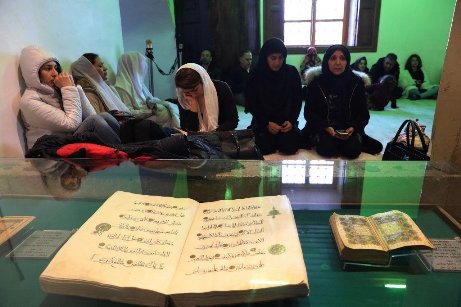

His legal method was defined by prioritising direct reading of the Quran, followed by traditions attributed to the Prophet Muhammad, then the conduct of the Prophet’s companions, followed by the use of analogy, consensus of the learned, custom, as well as practicality.

Abu Hanifa lived during a time when the people who knew the Prophet Muhammad had died or were born too young to have any recollection of him. This combined with the nascent Islamic Empire’s need for a coherent and firm legal structure created the conditions for the codification of Islamic tradition into law proper.

The theologian and his students therefore worked to apply Islamic principles to the legal problems that were coming up in their societies.

His legacy lies not just in the specific rulings he and his students issued but also in establishing the methodology needed to come up with them.

The scholar died at the age of 70 while under pressure from the Abbasid caliph, al-Mansur, to accept the position of chief judge. Abu Hanifa had refused the position, to the ire of the caliph, for fear that taking up an official role would compromise his independence.

Al-Mansur, incensed by the challenge to his authority, had Abu Hanifa imprisoned and the scholar later died in jail.

The episode did little to negate his legacy, however, with his Hanafi school firmly established and so many turning up to his funeral that the prayer had to be repeated five times in order to accommodate all those who had come to pay their respects. A shrine and mosque stand over his grave in Baghdad to this day.

Shah Abbas I

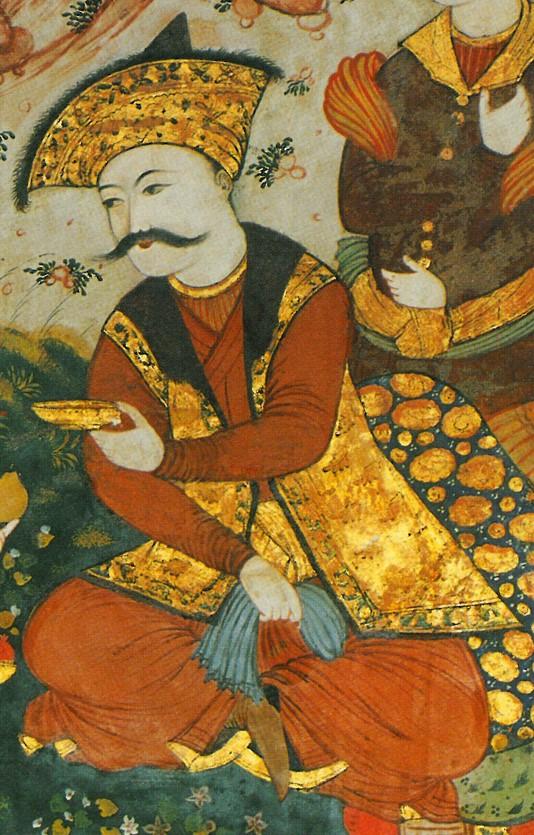

Shah Abbas I was born in January 1571, in Herat, in what is now modern-day Afghanistan. He was the fifth king of Safavid Iran, and considered to be one of the dynasty’s greatest rulers, earning the epithet “Abbas the Great”.

He assumed his position during troubled times for the Safavid Empire, with discontent within the army, economic uncertainty, and rival empires, such as the Ottomans looking to capitalise on the unrest.

However, Abbas, a master strategist, was able to centralise power by creating a caste of loyal soldiers similar to the Ottoman Janissaries, made up of conquered Christian peoples, such as the Circassians, Georgians and Armenians.

This elite group of soldiers took over civil and military administration, mitigating the influence of old warrior classes, such as the Qizilbash.

One of Abbas’s biggest accomplishments was the economic rejuvenation of Iran brought on by moving his capital to Isfahan in 1597-98.

During his reign, there was a heavy focus on architecture, trade and the arts. Literature and artists flourished under his rule, paving the way for acclaimed miniaturists including Aqa Riza and Mir ‘Imad.

Abbas was also noted for his relative tolerance of other faiths, allowing churches to be built for minority Christian communities and allowing missionaries to build bases to propagate their faith.

The Shah died in 1629, leaving a legacy that was difficult for his heirs to live up to. In 1722, Isfahan was besieged by a Pashtun tribe led by the Hotaki dynasty, which had rebelled against the Safavids. In the ensuing defeat, the Safavid dynasty collapsed.

Jamal al-Din Afghani

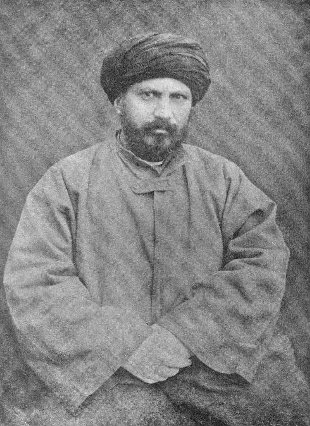

Sayed Jamal ad-Din Asadabadi, most often referred to as al-Afghani, was a 19th-century political activist, politician and journalist born in 1838 who travelled across the Muslim world advocating for pan-Islamic unity.

His exact place of birth is disputed, with some claiming that he was born in Afghanistan and others claiming that he was actually an Iranian who posed as an Afghan to avoid the accusation of being a Shia amongst his largely Sunni circles.

In any case, these sectarian differences mattered little to the activist, with much of his career spent on political agitation against western imperialists.

He began his career in British India, establishing a pattern of travel across the Muslim world, where he would work with local activists in Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Egypt to organise activism against foreigners.

The Indian experience, which coincided with the Indian Mutiny against British rule, is widely seen as a turning point in his political development and the formation of his anti-western outlook.

In 1866, al-Afghani took up a post in the government of Afghanistan, travelling extensively, including to Egypt, France, Turkey, the United Kingdom and Russia.

The crux of his ideology was pan-Muslim unity and that the only way to overcome western interference in the Islamic world was on the basis of common struggle.

Though opposed to western interference and colonialism, al-Afghani was an advocate of modern approaches to science and technology and believed that Muslims could only develop in terms of civilisation without the exploitative foreign presence in their lands.

Some of al-Afghani’s most notable work took place in Cairo, where he stayed from 1870-1879. In Cairo he taught Islamic philosophy and exposed students to his ideas on political reform.

There he got involved in Egyptian nationalist and anti-British politics, encouraging his followers to form political newspapers. One of his followers, Mohammed ‘Abdu later became the leader of the modernist Islamic movement; another, Saad Pasha Zaghlul, founded the Egyptian nationalist Wafd party.

Al-Afghani died of cancer in Turkey in March 1897, where he was buried. The Afghan government asked for his remains to be returned to Afghanistan in 1944, where a mausoleum was built in his memory.

The activist and scholar is widely considered to be one of the founders of the pan-Islamic movement.

Ibrahim ibn Adham

Ibrahim ibn Adham, sometimes referred to as Ibrahim Balkhi, was born in Balkh, Afghanistan, in 718CE to an aristocratic Arab family, but would go on to be known for his renunciation of material comfort and life as an ascetic.

The mystic helped influence the development of Sufism and was praised by Rumi, who recounted his legend in his work, the Masnawi.

In a story that echoes that of Gautama, the Buddha, Ibn Adham chose the ascetic life after giving up his throne, believing it was impossible to find God while distracted by luxury.

In one account, he comes across a camel herder looking for his animal on the roof of his palace. When Adham expresses his incredulity that a camel could ever make it to the roof, the man retorts that it was equally incredulous to look for God amidst material wealth.

The experience is said to have led to an epiphany, after which ibn Adham took on the life of a wise sage, traveling across the region and eventually passing away in Syria in 776CE, where his tomb is now located and has since been turned into a shrine.

Ibn Adham features frequently in Sufi legends, where miracles and encounters with divine beings, such as angels, are attributed to him.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Post Disclaimer

Disclaimer: Five people from Afghanistan who shaped Middle Eastern history By Nadda Osman - Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Latheefarook.com point-of-view