For Muslims, the Hajj is seen as an opportunity for new beginnings and can be the most transformative – and even transcendent – experience of their lives.

While a version of the ritual was performed in Arabia before the Prophet Muhammad began preaching his message, the Islamic rite dates to 628 CE.

That was the year the prophet and his followers were allowed to perform the pilgrimage after a treaty with Meccan clans put a halt to years of conflict.

The following year in 629 CE, Muslim armies conquered Mecca and removed all idols from the Kaaba and the area surrounding it, an event that marked the end of polytheistic practices in Mecca and the start of exclusively monotheistic worship.

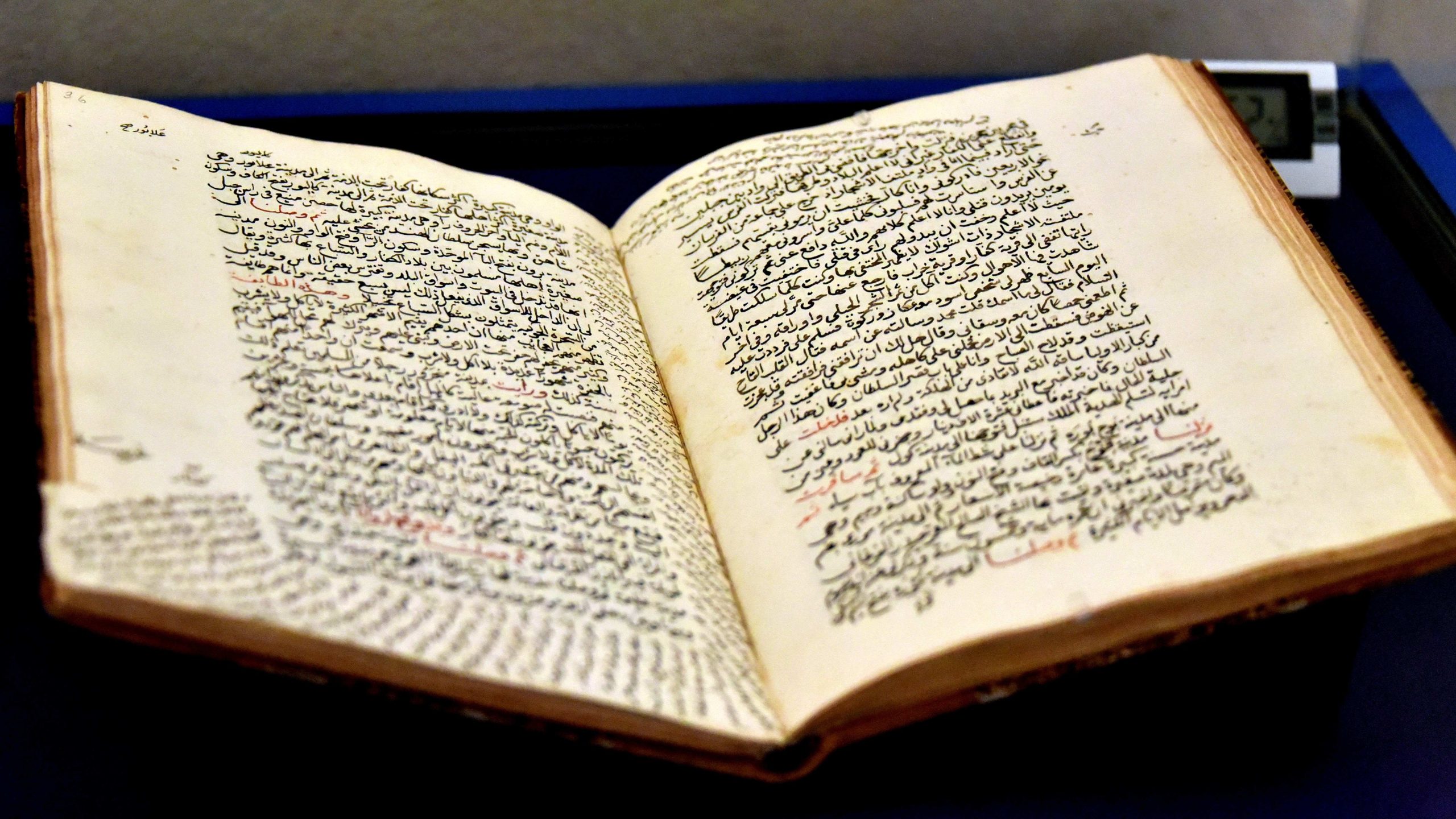

The earliest descriptions of the Hajj are largely third-person accounts recorded in the hadith, or narrations attributed to the Prophet Muhammad.

One of the most notable early records of the early Hajj is the “farewell pilgrimage”, during which the prophet announced the completion of his prophetic career and delivered his final sermon before his passing in 632 CE.

In the speech, the Prophet Muhammad delivered a famous affirmation of Islam’s racial egalitarianism, one that is exemplified during the pilgrimage.

“All mankind is from Adam and Eve,” he said, before continuing: “An Arab has no superiority over a non-Arab nor a non-Arab has any superiority over an Arab; also a white has no superiority over black nor does a black have any superiority over a white, except by piety and good action.”

That is a sentiment that would resonate with Muslims hundreds of years down the line and provided the context for Malcolm X’s epiphany on the brotherhood of all people during his pilgrimage in 1964.

Here Middle East Eye looks at six accounts of the Hajj throughout history.

Ibn Jubayr in 1184

One of the earliest surviving first-person accounts of the Hajj is by the Spanish Arab geographer Ibn Jubayr and dates to the late 1100s, a period marked by turmoil in the Middle East amid the collapse of the Fatimid Empire and the establishment of a united Muslim empire under the warrior Saladin.

Legend has it that Ibn Jubayr was forced by his patron to drink wine, and so in order to expiate his sins, in 1183 he set off on a pilgrimage to the Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina, stopping in Egypt along the way.

Ibn Jubayr provides a detailed and dispassionate account of the Hajj pilgrimage in April 1184, which corresponded to the Islamic year 579 AH. A modern reader can nevertheless glean some interesting insights into what the Hajj was like in the period. Some aspects may seem bizarre while others will seem familiar.

For example, the Spaniard warns of the threat posed by bandits from the Banu Shu’bah tribe, who despite the sanctity of the event “make raids on the pilgrims on their way to Arafat”.

More familiar will be the idea of the “luxury Hajj” with wealthy medieval Muslims paying large sums to experience a comfortable trip.

Ibn Jubayr writes: “The encampment of this emir of Iraq was beautiful to look upon and superbly provided, with large handsome tents and erections, and wonderful pavilions and awnings, and of an aspect such that I have never seen more remarkable.”

One dramatic episode during his pilgrimage was the outbreak of violence between Black natives of Mecca and visiting Turkic pilgrims from Iraq, in which some people were hurt.

“Swords were drawn, arrow notches were put to the bowstring, and spears were thrown, while some of the goods of the merchants were plundered,” Ibn Jubayr writes of the chaos.

Ibn Battuta in 1325

Another Hajj pilgrim, who travelled two centuries later, was Ibn Battuta, a Moroccan jurist and one of the most famous travellers in the medieval world.

Born in 1304, the Amazigh writer travelled from his native Morocco throughout Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and China.

At the age of 21, Ibn Battuta left his home country for the Hajj pilgrimage and embarked on an odyssey from which he would not return home until a quarter of a century later.

In his masterpiece, Ar-Rihla (“The Journey”), the Moroccan describes the various rituals of Hajj, like Ibn Jubayr before him, including the stoning of the devil and the sacrifice of an animal at the climax of the pilgrimage.

Like his Andalusian predecessor Ibn Jubayr, Ibn Battuta rarely goes into his own feelings and experiences, besides the intermittent prayers included within his writings.

Yet his excitement at seeing the Kaaba for the first time comes shining through in one description, where he describes the cloth covering of the structure as: “A bride who is displayed upon the bridal-chair of majesty, and walks with proud steps in the mantles of beauty.”

Evliya Celebi in 1672

In the 17th century, the Turkish noble Evliya Celebi credits a dream for his decision to travel across Anatolia, eastern Europe, the Caucuses, and much of the Middle East.

In the vision, a young Celebi encounters the Prophet Muhammad inside a mosque and instead of asking for his intercession on the Day of Judgement requests that he be allowed to travel.

The Prophet gave his consent and what followed was a decades-long journey across the Ottoman Empire and its neighbouring regions.

Celebi’s travels are recorded in the Seyahetname (“Book of Travels”) and are a mixture of actual events and some that stretch the limits of credibility.

For his pilgrimage, Celebi travels down the Anatolian coast through to Jerusalem before joining a Hajj caravan in Syria.

As a Turkish aristocrat, Celebi had access to senior Ottoman officials, as well as local tribal leaders, including the Sharif of Mecca.

His journey to Mecca was part of a heavily armed Ottoman caravan, which was needed to deter bandits who preyed on pilgrims travelling through the desert terrain.

When he finally reaches Mecca, the Ottoman traveller provides rich descriptions of the customs and the people of the city.

“The people of Mecca are dark-skinned, some of them reddish or brownish, with eyes like gazelles, sweet speech, rounded faces, keeping their own counsel, gentlemen of pure Hashemite lineage,” he writes of the residents of the holy city, who he says worked mostly as merchants.

Another notable aspect of Celebi’s account of the Hajj is his descriptions of the commercial element of the pilgrimage.

While not averse to exaggeration, his account includes the purchase of up to 50,000 camels for the pilgrimage by Damascene pilgrims from Arab tribes, who also purchase goods from the pilgrims.

“The Arab tribesmen get rich as well and come here once a year with their wives and children to buy precious stuffs,” Celebi notes.

Richard Burton in 1853

Not a genuine pilgrim and not a Muslim, the British adventurer Richard Burton represented a trend in Europe that was fascinated by the Islamic world and its rituals.

As a British soldier in India, Burton was fluent in dozens of languages including Arabic, Persian, and Pashto, and was also a renowned translator of works, such as The Arabian Nights and the Kama Sutra.

In order to witness the Hajj, Burton pretended to be a Pashtun tribesman and entered the Muslim holy city of Mecca with a caravan that had departed from Medina.

The feat was not unusual for European adventurers at the time but what made Burton’s adventure notable was the detailed descriptions of the Hajj he subsequently produced. These reveal just as much about the way Europeans viewed the Muslim world as they do about the events being recorded.

Describing his fear of being caught out during a visit to the Kaaba, he says: “A blunder, a hasty action, a misjudged word, a prayer or bow, not strictly the right shibboleth, and my bones would have whitened the desert sand.”

He is also one of the few non-Muslims to describe first-hand the ritual associated with the Hajj: “First I did the circumambulation of the Haram. Early next morning I was admitted to the house of our Lord; and we went to the holy well Zemzem, the holy water of Mecca, and then the Ka’abah, in which is inserted the famous black stone, where they say a prayer for the Unity of Allah.”

Muhammad Asad in the 1920s and 1930s

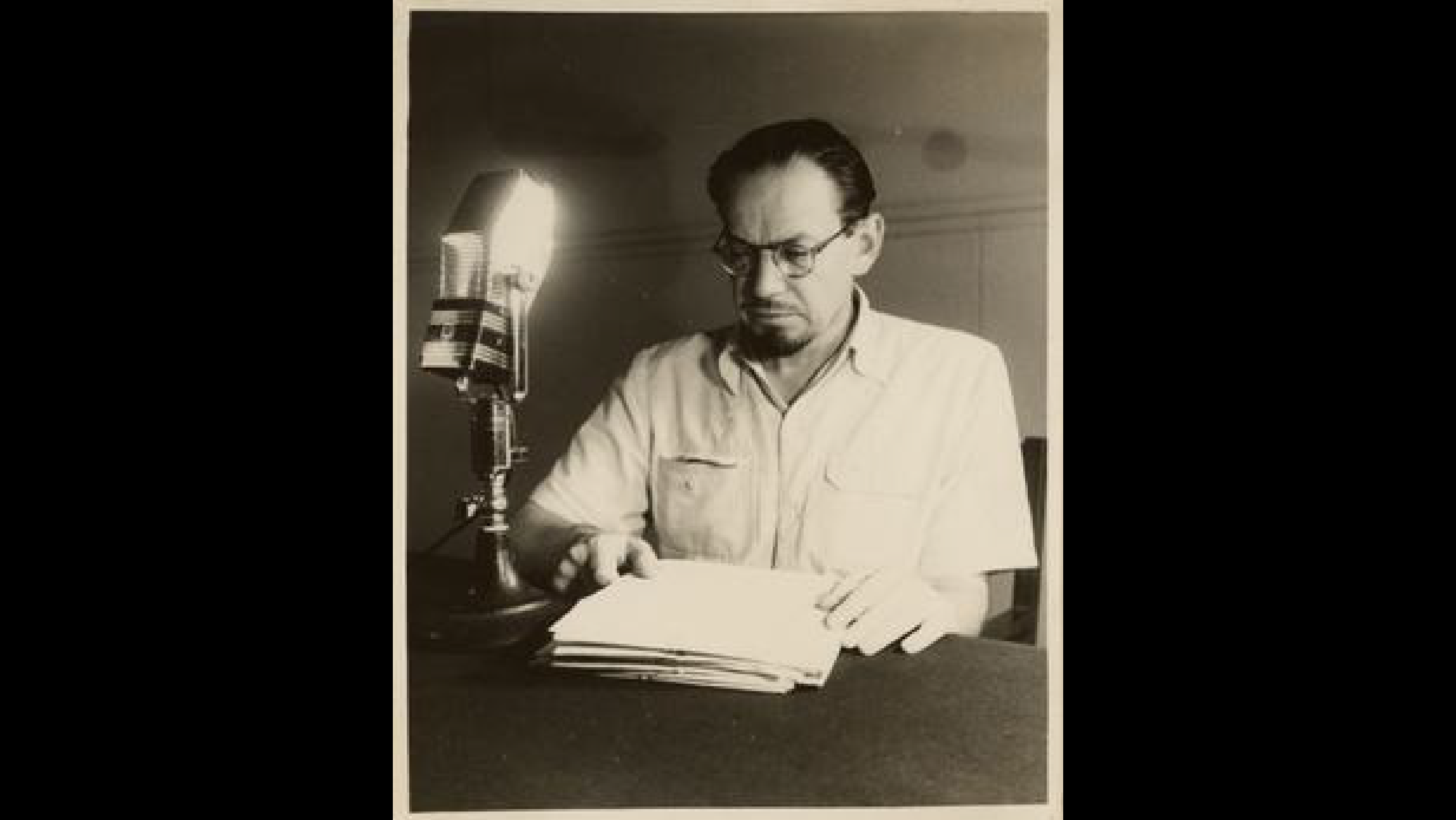

Not all Europeans who wanted to partake in the Hajj were curious Orientalists. One example of a genuine believer in Islam was the writer and journalist Muhammad Asad, who wrote about the spiritual symbolism of Hajj in his autobiography, The Road to Mecca.

Born in 1900 in the Ukrainian city of Lviv to a family of Austro-Hungarian rabbis as Leopold Weiss, Asad moved to the British Mandate of Palestine in the early 1920s and quickly developed an interest in the Arabic language and Islamic culture.

At 26, he converted to Islam and migrated to the fledgling state of Saudi Arabia, which had conquered the holy cities of Mecca and Medina in 1924.

There he became a close confidante of Saudi Arabia’s founder, King Abdulaziz, who retained him as a political advisor.

While living in the country, Asad performed the Hajj pilgrimage five times – experiences that had a profound effect on the young Austrian.

Describing the tawaf ritual, in which Muslims circumambulate the Kaaba seven times, he wrote: “The Kaaba is a symbol of God’s Oneness; and the pilgrim’s bodily movement around it is a symbolic expression of human activity, implying that not only our thoughts and feelings all that is comprised in the term ‘inner life’ but also our outward, active life, our doings and practical endeavours must have God as their centre.”

Finding himself in the midst of a diverse crowd of Muslims, hailing from Africa, South East Asia, and India, Asad further describes the state of transcendence he felt performing the ritual.

“I walked on and on, the minutes passed, all that had been small and bitter in my heart began to leave my heart, I became part of a circular stream – oh, was this the meaning of what we were doing: to become aware that one is a part of a movement in an orbit? Was this, perhaps, all confusion’s end?” He writes.

Asad went on to become a diplomat for the newly created state of Pakistan and died in the Granada region of Spain in 1992.

Malcolm X in 1964

One of the most famous accounts of the Hajj and one that demonstrates the ability of the ritual to transform a person was Malcolm X’s pilgrimage in 1964.

The Black nationalist had suffered isolation and threats to his safety after his split from the Nation of Islam (NOI) over the preceding years.

Until the journey to Mecca, the former NOI spokesman had advocated a hardline separatist solution to the persecution of African-Americans.

However, during the Hajj he was exposed to Islam’s approach to race relations for the first time.

In the wearing of the Ihram – the white cloths worn by pilgrims – he saw the melting away of differences of colour, class, and origin. An observation that catalysed a profound shift in his views.

In a letter to a friend after the experience, he wrote of his white co-religionists: “Their belief in the Oneness of God had actually removed the ‘white’ from their minds, which automatically (changed) their attitude and behavior toward people of other colors.

“Their belief in the Oneness of God has actually made them so different from American whites, their outer physical characteristics played no part at all in my mind during all my close associations with them.”

Malcolm X remained a staunch critic of white supremacy until his death in February 1965, a little less than a year after his pilgrimage. But in the Hajj he saw a way in which racial differences could be overcome.

Post Disclaimer

Disclaimer: From Ibn Battuta to Malcolm X: How six historic writers described the Hajj By Shafik Mandhai - Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Latheefarook.com point-of-view