From Algeria to Iraq to Lebanon, demonstrators are calling for change. What can the events of the 2011 uprisings teach them?

On 17 December 2010, Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi, humiliated by years of police harassment, set himself on fire in the city of Sidi Bouzid – a solitary act of protest that sparked a wave of anti-authoritarian uprisings across the region.

The subsequent Arab Spring, as it was known, was largely crushed by counter-revolutionary state forces desperate to entrench the status quo. Ten years later, people across the region are still setting themselves on fire in protest, from Sudan to Lebanon to Egypt.

The conditions that spurred the Arab uprisings, including government corruption, failed economies and deteriorating social services, have only intensified in many countries, exacerbated by 2020’s Covid-19 pandemic. The widespread failure of regional governments to tackle these underlying causes has led to Arab Spring 2.0: a new round of uprisings in which protesters demand a better quality of life.

Marwan Muasher, a former Jordanian diplomat who authored The Second Arab Awakening, tells Middle East Eye: “Arab Spring 1.0 could have resulted in social peace if Arab governments understood the need for new social contracts and the need for more open political systems, and the need to fight corruption institutionally.

“Most did not choose to do that, and instead they entrenched themselves, and the deep state came back very strongly.”

Protesters are again raising their voices – but this time, as analysts have pointed out, they have learned key lessons from the past.

1. The wall of fear can be broken

One important feature about the 2010-11 uprisings was that they showed the wall of fear that dominates the region could be broken, says Dalia Ghanem, a resident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut.

Despite the repression that followed the uprisings, this new understanding opened up fresh political and socioeconomic possibilities. The increased prominence of social media enabled further discussion of these ideas in online forums.

“Arab citizens broke the status quo, and that is, by itself, an achievement,” Ghanem says. “Since then, autocrats fell and people woke up and decided that they deserved better, and that the post-colonial social contract was no longer working.

“[Today] citizens are asking for their place in decision-making and are renegotiating their citizenry. What does it mean to be an Arab citizen?”

‘Citizens are asking for their place in decision-making and are renegotiating their citizenry’

– Dalia Ghanem, Carnegie Middle East Center

Tunisia was the only country swept by the Arab Spring that did not devolve into civil war or see the return of autocratic rule. But Arab rulers, Muasher says, failed to learn their own lessons about the importance of political change.

Much of the region benefitted until recently from high oil prices, and the foreign investment which that attracted. But when those prices took a dive, overseas revenue dried up. Without sufficient financial resources to maintain social peace, Muasher says, many autocratic rulers have now lost the cover that allowed them to tamp down the first round of Arab uprisings back in 2011. One decade later, protesters have increasingly less to lose from confronting these regimes.

Jade Saab, who edited A Region in Revolt: Mapping the Recent Uprisings in North Africa and West Asia, says: “[The first round of Arab uprisings] helped in the removal of what people in the streets are referring to as ‘the barrier of fear’, the idea that change is possible and should be sought at a fundamental level, that demanding change in living conditions alone is not enough.”

2. Dominate public spaces

During the Arab Spring, public spaces, such as Cairo’s Tahrir Square, came to symbolise the collective voice of demonstrators. Egyptian protesters occupied the square for more than two weeks amid state-sanctioned violence, including attacks by pro-government protesters on camels and horseback. Despite this, demonstrators continued to demand an end to the regime of Hosni Mubarak. On 11 February 2011, their wish was granted.

Egypt’s short-lived experiment in democracy then morphed into an autocracy more repressive than the Mubarak era. Mohamed Morsi, the country’s first democratically elected president, was ousted in a 2013 military coup by General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who has since launched a crackdown on dissent.

But, Saab says, the idea of what can be achieved through collective public gatherings and presence is still pertinent. The first wave of protests normalised strategies that were then adopted during the second, he notes.

“The most common one is the occupation of public spaces, which became places of creating and revising the identity of the whole nation, as well as a wellspring of art and culture.”

Last year, for example, as Iraqis flooded the streets in protest against the country’s corrupt elite, Baghdad’s “Turkish restaurant” – a dilapidated structure overlooking the city’s central Tahrir Square – became a headquarters for revolutionaries. One protester said it was destined to become “the history of the revolution in Iraq”.

In Beirut, Martyrs’ Square emerged as the epicentre of the uprising that started unfolding last October, with a six-metre-high portrait of a raised fist, the revolution’s symbol, as its centrepiece. Protesters have used the space to discuss the country’s political problems, but also to sing, dance and celebrate the potential for a new future.

3. Develop social forces

The first round of Arab uprisings in 2010-11 was followed by a period of relative quiet across the region. Many people were wary of protesting again, given how uprisings in Syria, Libya and Yemen had spiralled into civil wars that devastated countries, killed hundreds of thousands of people and displaced millions.

This, Saab says, “served as ammunition for regressive regimes in the region to suppress any popular mobilisation and paint them as nothing more than ‘chaotic'”.

The social protest movements that were active in 2010-11 were understandably under-developed – they had, after all, spent decades in the grip of authoritarian societies.

But, Saab says, the events of the Arab Spring helped such groups develop and mature. “Iraq, Iran and Lebanon witnessed nationwide protests between 2010 and 2019, but they were issue-focused protests,” he says. “It was those movements that helped create a new layer of activists. These countries had to go through their own process of maturation, quite independent of 2011, but knowing that a general uprising against the ruling class was always around the corner.”

Muasher says that the latest round of protests has been more peaceful. Demonstrators in Algeria and Sudan in the past two years, he observes, achieved broad support by eschewing violence.

The events of the Arab Spring helped social protest movements develop and mature

Magdi el-Gizouli, a Sudanese academic and fellow of the Rift Valley Institute, notes that the first cycle of the Arab Spring “ushered in a new type of mass engagement in politics, a pattern of action and a new political vocabulary and grammar of operation”.

The common denominator for many of the protests was, Gizouli says, an often-confused demand for social freedoms. But once in place, such movements were unable to deal with what followed. After leaders were deposed, there was no real plan for how protesters’ demands could be implemented on a political level.

“[In Egypt] powerful forces with deep pockets were quick to approbate and subvert the secular themes of the revolution, and indeed soon abolished the liberal freedoms discovered in the moment of revolt,” Gizouli says.

It leaves today’s protesters still grappling with a key question: how to themselves secure the goals of their own revolutions.

4. Go beyond superficial change

The biggest lesson for protesters in 2020, looking back on events one decade ago, is that genuine change cannot happen overnight. Superficial concessions, such as the replacement of one figurehead with another, do not lead to genuine political reform. Changing to a new political model takes time and consistent pressure.

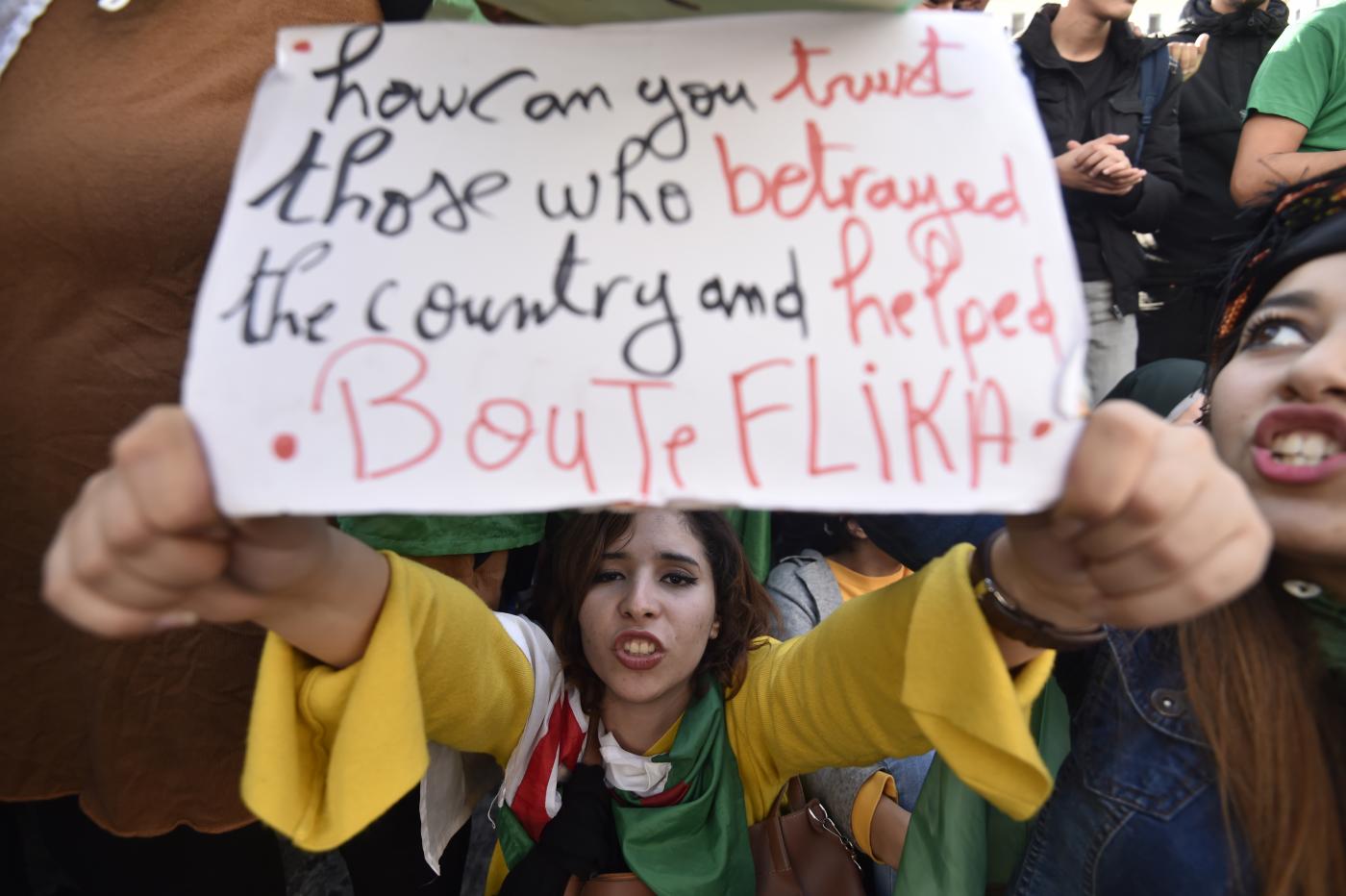

Khalil al-Anani, a senior fellow at the Arab Center in Washington, says it was notable that protesters in Algeria last year remained on the streets even after former President Abdelaziz Bouteflika left office.

“They didn’t repeat the mistakes of their Egyptian counterparts, who left Tahrir Square after 18 days of protests when Mubarak stepped down,” he says. “They insisted on turning power into the hands of civilians, and not to a military leader, which is a crucial step towards the reconstruction of the civil-military relationship in Algeria.”

Likewise, Muasher notes that protesters in Algeria “were far more patient than they were before”.

Protests in Sudan also continued even after the removal of former President Omar al-Bashir, as activists urged the pro-democracy movement to resist a military takeover. After Bashir was ousted and replaced by a military council, protesters chanted: “The first one fell, the second will, too!” Ultimately, in countries grappling with Arab Spring 2.0, a return to the previous political order may no longer be possible.

But Gizouli says that unless there are fresh political structures that can translate social demands into practical steps, then mass protests, such as those in Algeria, Sudan, Iraq and Lebanon, will only be able to deliver “defeated heroes but no power to the people”.

The challenge, he says, “is to reinvent a political organisation suited for the current purpose of securing the right to the city – Beirut, Baghdad or Khartoum”.

5. Dig in for the long haul

The latest uprisings in places such as Lebanon and Algeria are anti-neoliberal in nature, Saab says. They are learning the lessons of what happened in 2010-11 in Tunisia, which was able to achieve democracy but is still plagued by the economic problems that afflicted the old regime.

The region, he says, will continue to see demands for fundamental change as long as the ruling classes fail to resolve the underlying problems. “Unrest is what gives rise to social movements, and not vice versa,” he says.

He also believes that protesters need to develop a unified political vision, with those seeking reform coming together as one movement – something that only Sudan has thus far been able to achieve.

MENA, like the rest of the world, has been hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic during the past year. Muasher says that this has been a gift to authoritarian systems, with restrictions on movement, emergency orders and fears about the spread of coronavirus preventing people from gathering in large numbers. “Covid-19 has slowed down the movements, but in my view it has not killed [them],” Muasher says.

The impact of the virus, however, has been a double-edged sword for governments, deepening the economic problems that drive many reform movements and making further protests inevitable.

“People are going to see, in my view, many iterations – not just 2.0,” Muasher says, noting that new lessons will be learned each time. “We are in a very peculiar situation where the old Arab order has died, politically, economically and socially, and the new order is having great difficulty being born.”

Anani predicts that young people will likely “flood the Arab streets once again whenever they have the opportunity to do so, and will remain rebellious until their demands for freedom, justice, dignity and representation are met”.

“The bullet of change has already been fired in 2011,” he says, “and it is only a matter of time when it will hit.”

Post Disclaimer

Disclaimer: Arab Spring 2.0: Five lessons from 2011 for today's protesters By Megan O'Toole - Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Latheefarook.com point-of-view