Three decades have passed since Israeli leaders first sat down with Palestinians at a public negotiating forum in Madrid. It is easy to forget that the concept of the two-state solution, which today seems outdated and unrealistic, was not on the international agenda at the time. At the 1991 conference, Palestinians were willing to accept some form of limited self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza, and even agreed to placate Israel by coming to the conference as part of a Jordanian delegation. Much has changed since those days.

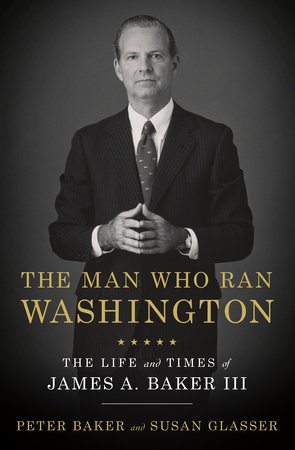

The main architect of the Madrid conference was James Baker, then the US secretary of state. In a comprehensive and well-researched biography, The Man Who Ran Washington, Peter Baker (no relation) and Susan Glasser, a journalistic husband-and-wife team with extensive Washington experience, reveal fascinating details about the manoeuvrings that led to the conference during George HW Bush’s presidency. They spent many hours interviewing Baker and US, Israeli and Palestinian officials, as well as reviewing Baker’s memos and diary notes.

Baker was brutal with Benjamin Netanyahu in a way that the Clinton and Obama administrations never dared to be

Baker and Bush were the last exponents of realism in US foreign policy before neocons took over the Republican Party and ideological “human rights” interventionists took over the Democratic Party. As such, they were not afraid to disagree publicly with Israeli leaders, and even to use the denial of aid as a way of applying pressure.

The Man Who Ran Washington covers other important Middle Eastern issues, including the first Gulf War and the Bush administration’s decision, after Kuwait was liberated, not to go on to topple Saddam Hussein. Coming across as Baker’s fans, the authors mention, but do not criticise, Bush urging Iraqis to rise up against Saddam. His words were not followed by any action, such as the use of air power, to stop the dictator from bombing Shia insurgents.

The book also covers the fall of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe and the reunification of Germany, as well as Baker’s role in domestic policy as former President Ronald Reagan’s chief of staff. But at the heart of its pages on the Middle East is the US relationship with Israel, which under Baker and Bush was more contentious than ever before or since.

Netanyahu banished

Baker was brutal with Benjamin Netanyahu in a way that the Clinton and Obama administrations never dared to be. Netanyahu, who was Israel’s deputy foreign minister at the time, had infuriated the secretary of state by claiming the US was being gullible in its dealings with Palestinians. “It is astonishing that a superpower like the United States which was supposed to be the symbol of political fairness and international honesty, is building its policy on a foundation of distortion and lies,” Netanyahu told the media.

An angry Baker instructed his officials that Netanyahu would be barred from entering the State Department. When Dennis Ross, a Baker aide, pleaded that this was too harsh a punishment, Baker “would just smile and say nope”. He eventually relented and allowed Netanyahu to come in to see junior officials, but refused to meet him personally throughout his time in office.

The Israeli programme of settlement construction in the occupied territories was a constant source of irritation for Baker and Bush. When Yitzhak Shamir, then the Israeli prime minister, told Bush during a White House visit in early 1989 that “settlements ought not to be such a problem”, the president wrongly believed this was an Israeli commitment to halt construction. When more settlements were announced two weeks later, Bush felt Shamir had lied to him and reportedly never forgave him.

It was no surprise that the issue came up again two years later, on the eve of the Madrid conference. Shamir was asking the US to guarantee housing loans worth $10bn for a new wave of Jewish immigrants from the Soviet Union. Baker and Bush were concerned that the money would be used for settlements in the West Bank and Gaza, and Baker persuaded Bush to postpone the loan guarantees.

Pressure from AIPAC

In a foretaste of the pressures that would plague later US presidents, Baker and Bush were regularly targeted by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), the powerful pro-Israel advocacy group, and its friends in Congress. Charges of antisemitism were trotted out.

In May 1989, Baker told an AIPAC conference: “For Israel, now is the time to lay aside, once and for all, the unrealistic vision of a Greater Israel … Forswear annexation, stop settlement activity, allow schools to reopen, reach out to the Palestinians as neighbours who deserve political rights.” Bush congratulated Baker on the speech, calling it candid, strong and fair, but senators from both US parties condemned it. They felt it was a sea change from Reagan’s warm embrace of Israel.

Bush resisted, and a few months later, called for an end to settlement building not just in the West Bank, but in East Jerusalem too – the first time a US president had referred to housing in the city as settlements.

Baker came under regular attack from the pro-Israel lobby. In March 1992, as Bush began his re-election bid, the New York Post ran a front-page headline: “Baker’s 4-Letter Insult: Sec’y of State Rips Jews in Meeting at White House.” In the accompanying article, former New York City mayor Ed Koch wrote that Baker had responded to criticism of the tough US approach to Israel by saying: “F*** ‘em. They didn’t vote for us”. After the word “they”, the Post had added in brackets “the Jews”. The quote was repeated endlessly by Baker’s critics.

The White House and State Department denied that Baker had said any such thing, but new variants of the distortion kept emerging, all with the suggestion that Baker was an antisemite. Jack Kemp, an eagerly pro-Israel former Congressman who had heard the alleged quote and told Koch about it, apologised to Baker years later and claimed that Koch had “mischaracterised” it. But the damage had been done.

Potential leverage

Yet Baker’s policies of pressure on Israel did pay off. In June 1992, Shamir’s Likud party was swept out of power in Knesset elections – a direct result, according to the Baker-Glasser biography, of Baker’s refusal to provide the $10bn for housing.

“Shamir lost the election in part because he couldn’t get the loan guarantee,” Moshe Arens, Shamir’s hawkish former defence minister, told the book’s authors. Likud was pushed out, and in came Yitzhak Rabin, leader of the Labor Party, who was much more open to negotiating a land-for-peace agreement with Palestinians. Baker had triumphed.

Initial Israeli resistance to threats of US sanctions may crumble as Israeli voters are reminded that Israel needs the US much more than the US needs Israel

But history does not repeat itself, and the parameters of the Israel-Palestine conflict are different today, three decades after Baker’s heyday (he is still alive at the age of 91). It could be that strong US leverage on Israel through withholding aid would help right-wing hardliners in Israel more than the country’s already weakened pro-peace camp, at least in the short term.

But there is no harm in trying the strategy again. The US has enormous potential leverage over Israel, thanks to the money it constantly pumps in. Initial Israeli resistance to threats of US sanctions may crumble as Israeli voters are reminded that Israel needs the US much more than the US needs Israel.

The lesson of Baker’s approach is clear: US pressure on Israel has worked to bring positive change in the past. It needs to be applied to do so again.

Post Disclaimer

Disclaimer: James Baker: The man who said No to Israel by Jonathan Steele - Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Latheefarook.com point-of-view