The birds were on their way down the Central Asian flyway — a migration path that crosses 30 countries from Siberia to the Indian Ocean.

“We would hide somewhere and … we don’t make any noise,” Ms Saroor recalls.

“[Then we’d watch] them coming and landing in the causeway areas and then catching fish and taking off as a huge group covering the entire sky.”

Up to a million birds stop at Mannar Island, off the north-west coast of Sri Lanka, to feed during the winter.

The Vankalai Bird Sanctuary on the southern tip of the island is protected by the Sri Lankan government and has been internationally recognised under the Ramsar Convention for its importance to both local and migratory birds.

Ms Saroor also remembers climbing the swollen trunks and gnarled branches of the baobab trees — trees synonymous with Africa, Madagascar and Australia’s Kimberley, but also found incongruously on her tiny island.

“Even though I fondly remember these baobab trees, one thing that I really remember is how … [members of the militant separatist group the Tamil Tigers] put the mutilated heads of the Indian peacekeeping forces on those trees.”

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam fought a 30-year civil war with majority Sinhalese Sri Lankan military, in an attempt to create an independent Tamil homeland in the north and east of the country.

Ms Saroor had already left the island to study in Colombo in 1990 when the Tamil Tigers forced her remaining family off Mannar Island, along with all the other Muslim residents.

Since the war ended in 2009, many displaced Mannar Islanders have returned to re-establish themselves in fishing and farming communities. But the trauma still lingers and there are tensions over land.

Against this backdrop, an Australian company has a plan to mine Mannar’s sands.

There are fears for the island’s fragile ecology, agriculture and fishing areas — and islanders are worried they could be displaced all over again.

Company’s drilling triples estimate of island’s minerals

Mannar is the biggest island at the base of a narrow chain of limestone shoals known as Rama Setu or Adam’s Bridge, which stretches 48 kilometres north-west to join India.

The island is 26km long by 8km wide and has rich deposits of the mineral ilmenite in its sand.

Ilmenite is the main source of titanium dioxide, a valuable white pigment used in things like paints, ink, plastics and cosmetics.

In 2018, Perth-based company Titanium Sands advised the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) it entered an agreement with Srinel Holdings Ltd to explore the extent of the island’s ilmenite reserves.

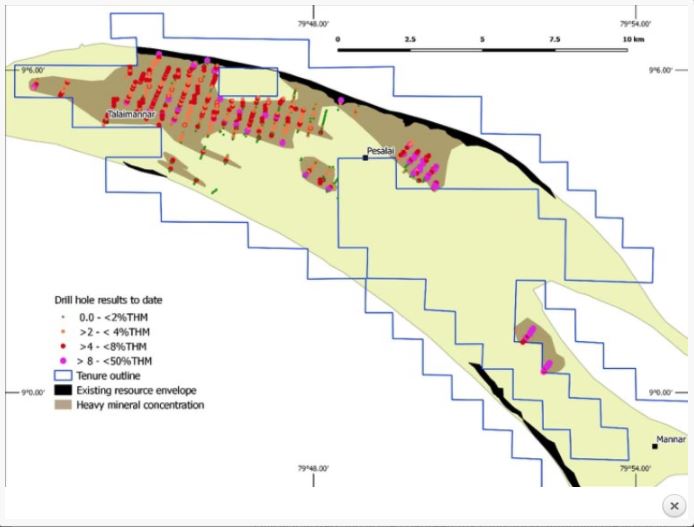

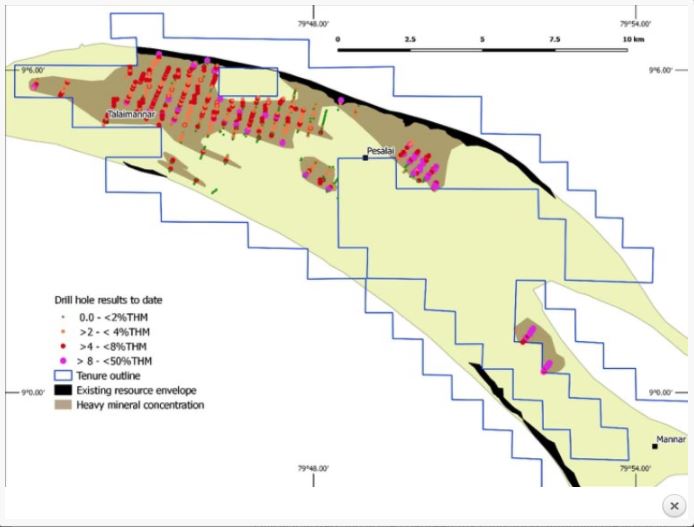

In May this year, the company announced their exploratory drilling had tripled the previous estimate — to a total of just under 265 million tonnes.

Managing director of Titanium Sands, James Searle, says the company is looking to mine an area of the island that is 2km wide and about 8km long.

“That’s probably over a 30-plus year lifespan,” he told ABC RN’s Science Friction.

“On an annualised basis that’s probably … in the region of between 10 and 16 hectares.”

But some Sri Lankan scientists and environmentalists say they have been inadequately informed about the project.

‘The machines are moving in’

Ms Saroor’s younger brother is one of those who have made it back to the island, where he has a coconut estate.

“The first time I heard about this Titanium Sands mining is from him,” Ms Saroor says.

Companies that Titanium Sands acquired started preliminary assessment with small-scale drilling on the island in 2015.

Throughout the totality of their study, which included a scoping study completed this year, the company drilled more than 3,000 exploratory holes with the deepest going down to 12 metres. The majority were between 1 and 3 metres.

According to Dr Searle, there has been no drilling in built-up areas of the island.

“The population on the island is largely concentrated in a town down the landward end of the island, called Mannar Town. There are other coastal villages, other settlements around the island,” he says.

“Our exploration work is only being undertaken on areas where there is no habitation and where there is no active agriculture.”

It’s some of those undeveloped areas of Mannar Island that concern ecologist Sampath Seneviratne, who studies Mannar’s birds.

“Flamingos must be the most charismatic and sought-after in terms of beauty,” he says. “[But] spoon-billed sand piper, one of the rarest birds in the world and one of the most iconic species that are on the verge of extinction right now, has been recorded in Mannar.

According to Dr Seneviratne, a public notice is usually issued when companies are given permission for mining exploration in Sri Lanka.

But he and his colleague at the Wildlife Protection Society only found out from a friend in Australia about the drilling, and they were surprised that local environmental groups knew nothing of the project.

“It was a big shocker, because how did people like us working in [Mannar] not know this?” he asks.

Company accused of illegal conduct by Mines Bureau

Earlier this year in June, Titanium Sands was accused of illegal conduct in local Sri Lankan media reports.

The Sri Lankan Geological Surveys and Mines Bureau (GSMB) — the government body responsible for issuing mining and exploration licences in Sri Lanka — reportedly said the company’s exploration was unlawful.

The GSMB told local media that under Sri Lankan law, Titanium Sands couldn’t legally acquire the rights to explore Mannar by purchasing the company (Srinel Holdings Ltd) that previously held the licences.

But Dr Searles says the GSMB was “incorrect” and was responding to misleading social media posts.

“The legal advice and the legal structures are in total compliance with the Sri Lankan regulations,” he says.

The ABC contacted the GSMB but did not receive a response.

In November, a committee was put together by the Sri Lankan Ministry of Industry to look into the claims of illegal drilling.

Titanium Sands presented its case to the Ministry of Industry, but Dr Searle says he hasn’t heard anything further.

At the time Science Friction went to air there was no information on the company website about the committee’s enquiries into the project.

Asked why, Dr Searle responded: “We received enquiries on all manner of things and we don’t consider it to be significant.”

The company has since added a statement that says it “is not being investigated” although they have “provided information to the committee” which they say confirms the validity of their licences.

It also stated that the company has “no intention of pursuing a project that potentially impacts a Ramsar-designated area”.

Mannar ‘promoted as a promising resource’

Environmental scientist and senior director of the Centre for Environmental Justice, Hemantha Withanage, says he is concerned he hasn’t heard anything about the committee’s enquiries since the Sri Lankan federal election in August.

But, he says, the picture Titanium Sands is painting for their shareholders is not all it seems to be.

“On their website, they’re promoting Mannar Titanium Sands as a promising resource,” Mr Withanage says.

“How can somebody promote like that, without going through the environmental impact assessment process and getting the government approval?”

“We are very, very concerned about what this company is going to do in Sri Lanka,” he says.

But an environmental impact assessment and public consultation are the next steps in the process, according to Dr Searle.

“That would eventually [lead to], we hope, granting of mining licences and ultimately development of the project,” he says.

Mining would ‘dramatically transform’ the ecosystem

Mineral sands mining is considered to have a fairly low impact on the environment compared to some other forms of mining.

The process doesn’t involve chemical separation of minerals such as in gold mining, or digging vast open-cut pits such as with coal.

Titanium Sands published material online showing the location of their resources including exploratory drill holes near the coast.

Daniel Franks, program leader of the development minerals strategic program at the University of Queensland, says Titanium Sands’ scoping study, released to the ASX in June this year, reveals the size of the planned mine is extensive and includes areas just a few metres from the beach.

If the operation was based in Australia, the company would be unlikely to be granted permission to mine those areas, says Professor Franks, who is not involved in the project.

“Mining to such a wide extent would dramatically transform the ecosystem. It would also limit the land uses that the community already has for the island,” he says.

Mining near active beaches can disturb coastal morphology and removing vegetation can leave sand dunes vulnerable to erosion.

Managing director Dr Searle stresses that his company may not end up being able to mine all the resources they’ve identified, should the mine go ahead.

He says the company doesn’t intend to mine near beaches on Mannar, and that there is no economic incentive for the company to do this.

“Those areas along the shoreline are of no interest to us whatsoever because we consider them to be environmentally sensitive. We are much more interested in the interior, one to three kilometres away from the nearest coastline.”

But Professor Franks says the company’s assertion that it has no plans to mine near the beach “appears contrary to the scoping study released to the ASX” and that an update to the ASX might be in order.

Ms Saroor is also afraid the mine could damage the island’s groundwater.

“Mannar gets the smallest amount of the rain in the whole of Sri Lanka. So we totally depend on groundwater,” she says.

Professor Franks says the extent to which a sand mine could disturb the groundwater on Mannar depends on how deep Titanium Sands digs into the ground.

“I think there is a potential to impact groundwater systems. We’ve seen that in Australia where there’s indurated layers in the sand, that are impermeable and that can hold water,” he says.

“But I think the bigger impact is just the surface disturbance that’s going to happen across the island.”

Dr Searle, however, says the project will not affect groundwater or disturb beach areas.

“If it was to affect the groundwater, we wouldn’t be doing it,” he says.

“This sort of operation … has occurred over the last 50 to 60 years [in Australia] with an excellent environmental record.”

‘The people on the ground have the right to say no’

Rather than displacing people, Dr Searle says the mine will create between 200 and 600 jobs and that 95 per cent of those employed would be Sri Lankan people.

But Ms Saroor, who is now an award-winning human rights activist, is concerned about the impact on a community recovering from war.

She believes Titanium Sands should not add to the trauma of a community that is still rebuilding.

“At the end of the day, they are investing in Sri Lanka to make profit,” she says.

“So, my message would be to them to make sure not to profit out of a community that has been suffering in the last 30 years of the war.

“Think about the impact not only on the environment, but also on the people, and [then] make their decision.”

Mr Withanage of the Environmental Justice Centre says he could support the project, if it can be proven to be done in a way that benefits the local community and earns its social licence.

He says the final decision on whether the mine goes ahead needs to rest with the Mannar people.

“It’s not the Australian citizens who are going to make that decision.

“It is the Sri Lankan citizens going to that place, Sri Lankan government agencies, Sri Lankan courts… So they have to make that information available to Sri Lankans first.

Post Disclaimer

Disclaimer: Mannar Island is a bird paradise that survived Sri Lanka's civil war. Now an Australian mining company wants its sand - Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Latheefarook.com point-of-view